Cassava is a primary food source for most indigenous peoples of Guyana. Many indigenous groups eat cassava in the form of cassava bread and farine, as well as regularly manufacture fermented cassava beverages.

According to Terry W. Henkel in his study “Parakari, an indigenous fermented beverage using amylolytic Rhizopus in Guyana”, most indigenous cassava fermentations involve prolonged cooking and exposure to salivary enzymes as the method of initially breaking down the starch to sugars (amylolysis), which subsequently are fermented to ethanol.

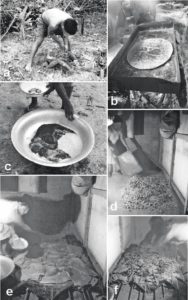

Parakari is a more complex cassava fermentation using an amylolytic mold in place of salivary amylolysis. In other words, instead of chewing, indigenous peoples utilise fungus to break down starch to sugars.

While fermented beverage production is nearly universal among indigenous Amazonians, parakari is unique among New World beverages because it involves the use of an amylolytic mold (Rhizopus sp., Mucoraceae, Zygomycota) followed by ethanol fermentation, he states.

Among the Wapishana of Aishalton village in the Rupununi whose fermentation process he studied, thirty steps were involved in parakari manufacture, and these he notes exhibited a high degree of sophistication, including the use of specific cassava varieties, control of culture temperature and boosting of Rhizopus inoculum potential with purified starch additives.

During the fermentation process, changes in glucose content, pH, flavour, odour and culture characteristics were associated with a desirable finished product. Parakari is the only known example of an indigenous New World fermentation that uses an amylolytic mold, likely resulting from domestication of a wild Rhizopus species in the distant past.

Henkel states that only three of the tribes currently manufacture parakari: the Wapishana, Macushi and Patamona. Production of parakari among the Wai Wai, who live to the south of the Wapishana in extreme southern Guyana, was noted early in the 20th century but now has ceased due to suppression by missionaries.

In his study Henkel finds that the origins of parakari fermentations are lost in antiquity. The overwhelming prevalence of fermented beverages throughout Meso- and South American indigenous cultures indicates a long-term, pre-Columbian practice.

Parakari production, with its exceptional degree of microbial manipulation, certainly has a long history. The Wapishana noted that the beverage has been around since the “beginning of time”; they have no cultural memory of a time without it.